TURBOSTAAT • Alter Zorn • LP/Tape

TURBOSTAAT • Alter Zorn • LP/Tape

Couldn't load pickup availability

PIAS Records

Turbostaat’s Eighth Album: Where There Were Once Seagulls and the Wadden Sea, Now There Are Pigeons and Concrete

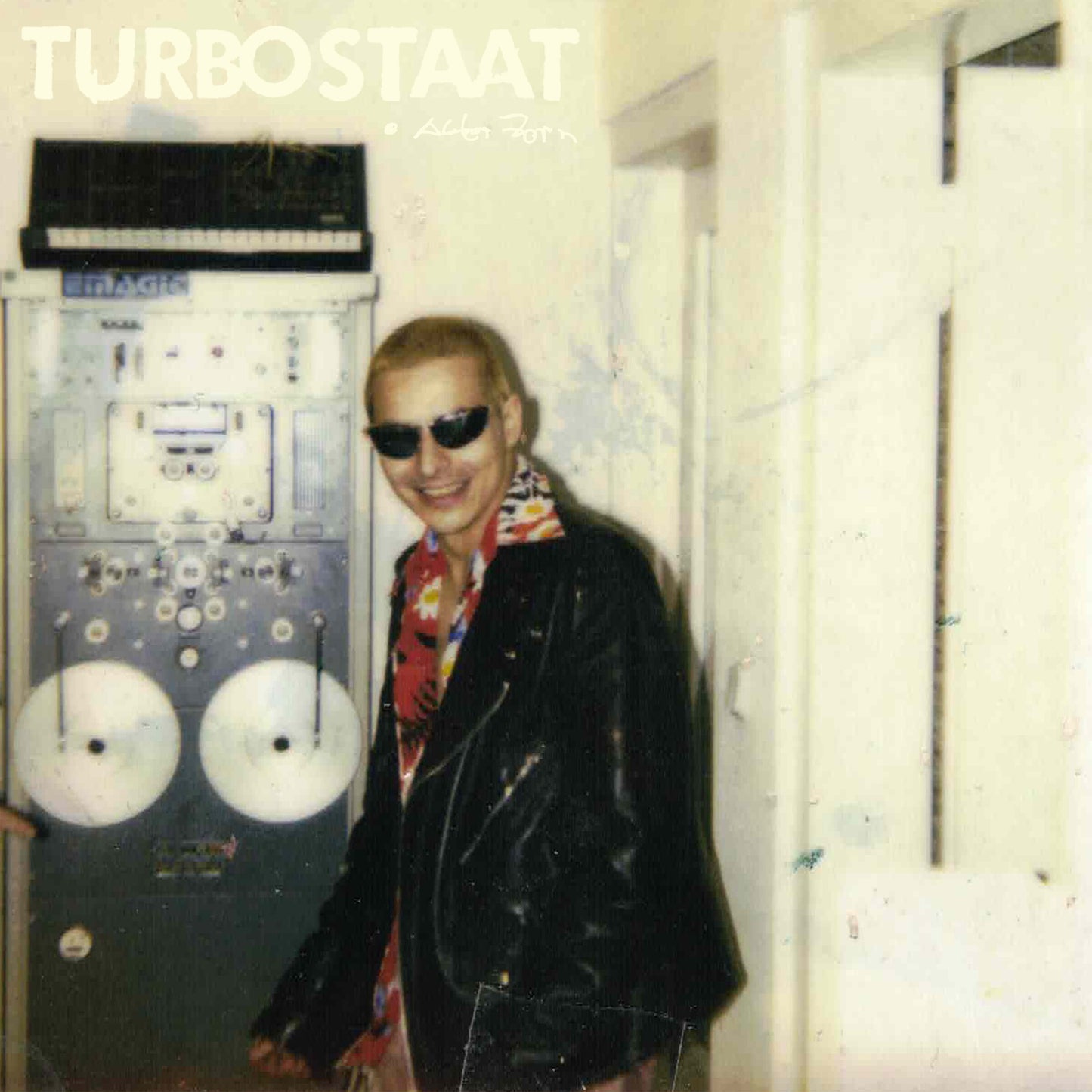

Young punk stands with a broad smile in a barren corner of a room, facing a worn-out tape machine; short-cropped, bleached hair, sleek sunglasses with thin metal frames, an old leather jacket over a colorful flannel shirt; a true Trainspotting aesthetic. The scene described may not be a typical album cover motif – yet it graces the cover of the new, eighth studio album by the band Turbostaat, hailing from Husum, Hamburg, and Berlin. The man at the center of this faded snapshot? Turbostaat’s long-time producer and sound engineer, Moses Schneider, in his late twenties—or perhaps his early thirties—certainly from a time before chamomile tea and high-end equipment. Dirt, anger, a desire to take action, the energy of new beginnings, and gritty pessimism—the raw punk spirit—these are the connections between that photo and the album it represents. The album, rightfully titled Alter Zorn ("Old Rage"), feels more like a debut than a late-stage release, gripping its listeners in a bracing, rough chokehold rather than offering a gentle embrace.

Alright, let’s be fair: Turbostaat have never exactly embraced their listeners with musical tenderness. Their sound has always been more understated and marked by North Frisian sobriety than by charm or cheerfulness—more longing than contentment, more noise, cryptic lyrics, and a grumpy expression than lighthearted antics. Turbostaat’s music has always been punk rock with the fog of the Wadden Sea in its lungs, ever since the band formed in 1999 in the rural province of Schleswig-Holstein—and still is, a quarter-century later.

Where there were once seagulls, the fog of the Wadden Sea, and endless grey horizons, now flocks of pigeons obscure the sky, smog-choked concrete towers dominate, and a goddamn statue of Bismarck, his oversized backside turned toward the trendy quarter, blocks the view of anything beautiful. Alter Zorn gazes down the "Monkey Street," into run-down corner bars where dark shadows pile up, upon "ruins between glass and steel," into metropolises filled with "glaring summer puke" and shards of broken mirrors, closing in on themselves—rarely staring out towards the open sea. What remains for the blurred protagonists of Turbostaat’s universe is the nagging loneliness—that angry, resigned feeling of not being able to "march along here." Alter Zorn paints a dystopian picture—a world somewhere between November chill and heatwaves, where dead swans pile up in ditches, tanks roll by, the air becomes scarce, the homeless embrace the streets, everyone pays for everything with a card, trembling in leather seats, spirits crushed, and, frankly, it’s truly “the end of the line".

Manufacturer information

Manufacturer information

Apparently, GPSR requires us to share our suppliers / manufacturers for this item with you. No idea why you need this info, but here you go: